America’s Battle Over Darwinism Was Personal

Darwin had fretted for years about the cataclysm that his book’s publication would cause. In the U.S, one opponent loomed over others.

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

This is an edition of Time-Travel Thursdays, a journey through The Atlantic’s archives to contextualize the present and surface delightful treasures. Sign up here.

In July 1860, The Atlantic Monthly’s readers were confronted, many for the first time, with Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. “Darwin on the Origin of Species,” the first of three essays by the Harvard botanist Asa Gray about Darwin’s 1859 book, instigated a torrent of letters in response, some intrigued, others scandalized. Emily Dickinson, it seems, remembered the experience of reading Gray enough to allude to it decades later. One hundred and fifty years after its publication, his essay spiked in readership on this website.

Gray, a scholar and naturalist, adopted the pose of a reader made uncomfortable by Darwin’s idea. “Novelties are enticing to most people: to us they are simply annoying,” his essay began. “We cling to a long-accepted theory, just as we cling to an old suit of clothes … New notions and new styles worry us.”

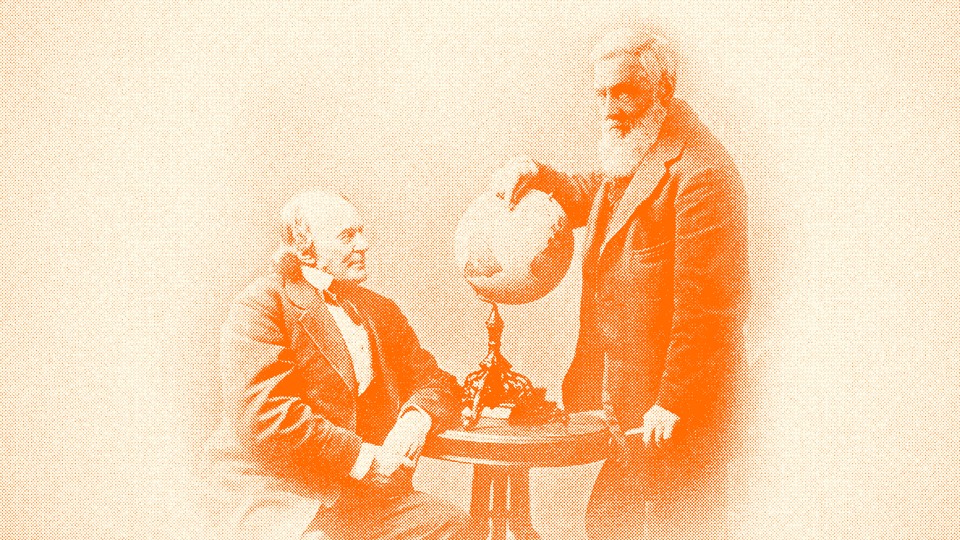

This was subterfuge. Gray was among the few confidants for whom Darwin had previewed the idea of natural selection, and he had supplied Darwin with key research about plant distribution. Darwin had fretted for years about the cataclysm that Origin’s publication would cause, and in the United States, one opponent loomed over others: Louis Agassiz.

At the time America’s most prominent scientist, the Swiss-born zoologist swapped theories with Ralph Waldo Emerson; Henry David Thoreau sent him a turtle specimen from Walden Pond; Oliver Wendell Holmes rhapsodized about him in this magazine. Agassiz, a colleague of Gray’s at Harvard, was a hit on the lecture circuit, where he performed a populist version of science that grated on Gray, who was establishing himself as a precise empiricist. (Gray snickered in a letter to Darwin that Agassiz’s Atlantic article on glaciers “will not strain your brain.”) Agassiz promoted the belief that God had created species in their exact geographical and hierarchical slots, where they remained unchanging. This anti-evolutionist notion eventually ruined his legacy, but in 1860, he was an imposing figure who could stomp out Darwinism the moment it reached America.

Gray did not maintain his ruse of reluctance in The Atlantic for long. By the end of his first article, he had overcome his professed misgivings about natural selection. In the second, the biographer Christoph Irmscher points out, he set about using his fellow professor’s arguments against him. Agassiz—“our great zoölogist,” Gray sniffed—had observed that earlier species contained combined characteristics that reappeared separately in subsequent animals. He called them “prophetic types.” Extinct “reptile-like fishes,” for instance, appeared to prophesy both the common fishes and reptiles. Gray wondered aloud: Didn’t natural selection explain Agassiz’s observation much better than his own baseless supposition did? “If these are true prophecies,” Gray continued, “we need not wonder that some who read them in Agassiz’s book will read their fulfilment in Darwin’s.”

After Origin’s publication, Darwin gifted a copy to Agassiz, along with a note swearing that he hadn’t sent the book as a provocation. Agassiz seemed to have been too appalled to finish it; despite his outraged marginalia (“this is truly monstrous”), he is believed to have ceased reading partway through. Still, he’d tolerated enough of natural selection that he reckoned he’d caught it in a tangle. “If species do not exist at all,” as he saw the upshot of Darwin’s theory to be, then “how can they vary? and if individuals alone exist,” he continued, in a critique quoted by Gray, “how can the differences which may be observed among them prove the variability of species?”

“An ingenious dilemma,” Gray allowed, before turning it around on his opponent. Agassiz maintained that species were “categories of thought” established by God. Even if this were true, Gray responded, that hardly stopped those categories from varying—God’s thoughts could presumably encompass all manner of change and multiplicity. And what, exactly, were these “categories of thought” Agassiz proposed, anyway? “Mr. Darwin would insinuate that the particular philosophy of classification upon which this whole argument reposes is as purely hypothetical and as little accepted as his own doctrine,” Gray wrote.

In other words, Gray suggested, Agassiz’s vision of a divinely segmented universe was nothing but metaphysical conjecture; he was, more or less, making stuff up. Against this, Gray submitted On the Origin of Species, which had been comprehensively researched and meticulously argued. Agassiz, the doyen of American science, suddenly found himself rendered not just unconvincing but unscientific.

Agassiz could only repeat his belief, more emphatically but less compellingly. He lost allies in Cambridge and gained critics in scientific organizations. Darwinism spread among his students. In 1864, Agassiz and Gray exchanged words on a train; Gray, Agassiz declared, was “no gentleman!” One of them was rumored to have challenged the other to a duel. Agassiz finally left for a research trip to Brazil. “It was clear to Agassiz’s friends,” Louis Menand wrote in The Metaphysical Club, “that it might indeed be a good idea for him to get out of town.”

A second line of attack lurked in Gray’s essays, one perhaps more fatal from our vantage point. Agassiz believed that races were created separately, were as immutable as animal species, and had been stacked by God with white people on top. Although he opposed slavery, his writings “lent scientific authority to those determined to defend the slave system,” the Darwin biographer Janet Browne noted. Gray, who like Darwin opposed slavery, took a shot at Agassiz’s pseudoscientific racism. “The very first step backwards makes the Negro and the Hottentot our blood-relations,” Gray wrote of the branching human lineage implied by Darwin’s theory of descent. “Not that reason or Scripture objects to that, though pride may.” If man emerged from a common origin, went Gray’s implication, then maybe a certain zoologist and the Black people who repulsed him were more closely linked than the zoologist preferred to believe. One can imagine Gray composing the line about “pride” with Agassiz’s aghast reaction to it in mind.

Agassiz’s resistance to evolution diminished his reputation during his lifetime, but his racism posthumously doomed it. His name has been removed from schools and natural landmarks; Swiss towns have faced a call to rechristen the Agassizhorn mountain. But in 1860, that was all in the future. A change in The Atlantic Monthly’s editorial leadership shortly after the publication of Gray’s essays favored Agassiz; he contributed frequently to the magazine well into old age. Asa Gray, the victor in the fight over the American reception of Darwinism, and in some ways over the future of American science, never appeared in these pages again.