Mapping the Anxiety About College Admissions

In which parts of the country is the hysteria worse?

This week I came across another version of one kind of news article I find fascinating for some reason—what I think of as the "college-anxiety" article. These pieces have, as their core premise, the anxiety that emerges when students and parents have their eyes and hearts set on a small range of elite colleges and universities, admission to which is highly competitive and, for most applicants, quite unpredictable. The uncertainty causes the anxiety.

These news items come in different versions, ranging from those that focus, like this one I read in the Boston Globe, on individual kids who are anxious (or whose parents are anxious for them), to those that focus on whole schools, districts, or regions where the college-admissions mania has blown through the roof, to those that center on the various growth industries that are feeding on (and also revving up) that anxiety.

Lately, I've been learning ESRI's ArcGIS geographic-information-systems software (read: mapping software) as part of my work with Jim Fallows and his wife Deb on their American Futures project here at The Atlantic. So, when I saw the college-anxiety article in the morning newspaper, I started to wonder how one might go about mapping this social anxiety. (Not everything lends itself to mapping, of course, but I find myself bound by the law of the instrument: With this hammer in my hand, everything looks like a nail.) A warning: I'm new to this mapping business, so neither my thinking nor my processes are very sophisticated. But let me take you through my inelegant steps.*

I suppose there may be data available somewhere from opinion surveys that highlight those parts of the country where people are subject to this admissions-related disquiet, but I doubt it, and, in any case, I wouldn't know how to find the data. But maybe there's a proxy measure or indicator of it. It strikes me that the presence of private college-admissions consultants in an area might be a signal.

When students or families have the financial means, one way they often deal with their anxiety (or manifest it) is by retaining the services of a college-admissions consultant, a hired gun, who professes to be able to guide students and their families to desired admissions outcomes. Their services include providing input and advice (some say more than advice) on application essays, tutoring, prepping students for the SAT, and the like. Some families use these services to short-circuit the tensions that arise in the home when the college-application process gets underway: It's helpful to have a buffer between parents and teen—some other party to monitor the process, provide advice, and so forth.

My point here isn't to probe the interstices of this industry or to criticize it, but to use it as a proxy for getting at the geographic distribution of social anxiety over college admissions. (Note that I'm focusing here on anxiety over admission to extremely selective, elite colleges. There shouldn't be any anxiety over admission to college generally. Anyone can get into some college these days.)

I've always assumed that the hysteria over admission to elite colleges is largely a phenomenon that is concentrated in certain regions of the country (the Northeast and mid-Atlantic, sophisticated urban centers in the middle, and cities on the West coast) where people with particular cultural or socio-economic profiles concentrate—those who care inordinately about the prestige, real or imagined, conferred by that magical letter of admission to an elite institution. Might we, therefore, expect that college-admissions consultants tend to be concentrated in those areas? Is there a way to find out if my sense of this is correct? Let's see.

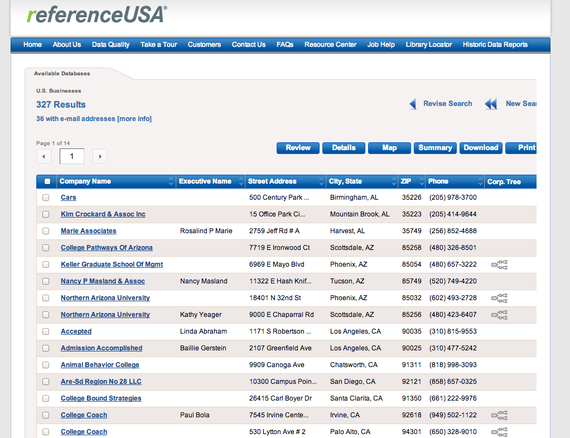

First, how to find college-admissions consultants? I decided to use ReferenceUSA.com, a business database, to locate college-admissions consulting businesses by their SIC code, which is 829989. I queried the database for all such businesses in the United States. It returned 327 records—a number I thought surprisingly low, given the number of such companies I'm aware of in my own area here in greater Boston. I selected the particular record features I wanted and then downloaded the data into an Excel spreadsheet.

I then opened my account at ESRI's ArcGIS and uploaded a .csv version of the Excel file to my content at ArcGIS, giving it the appropriate name and tags. Once the data (now known in ArcGIS as a "feature layer") were uploaded, I was able to put it into a map, where I could choose what kind of icon or symbol I wanted to use for these businesses (I chose a black diamond) and configure the pop-up box that appears when an eventual viewer (you) clicks on a particular item on the map. So, here's the map. You can zoom in and out. And you can click on an individual black diamond to see the name of the firm in that location.

Good enough. But now my anxiety started to kick in. The resulting map showed precisely what I expected—concentrations of such companies in the geographic areas I mentioned above. But how can I know if these data are capturing an accurate picture of the universe of college-admissions consultants (never mind whether this is an accurate map of social anxiety over college admissions)? I can only assume the data are good, but what if they're incomplete?

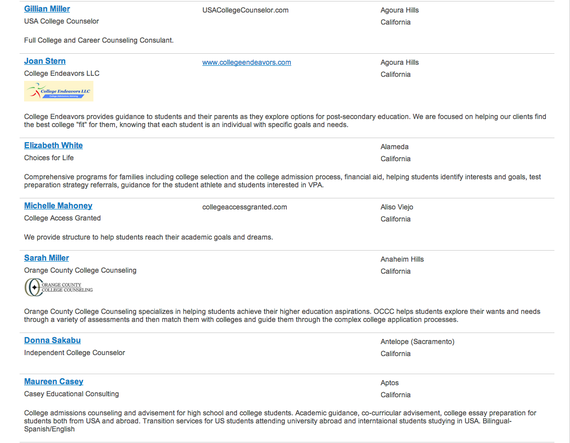

To get another sense of this particular slice of American business, I searched for trade associations or professional associations that represent people and companies in this line of business and found the Higher Education Consultants Association (HECA) and the Independent Educational Consultants Association (IECA). On the HECA website, I see that they categorize members by the types of services provided, with 811 listed as providing "college selection" services, 802 providing "application guidance" services, 803 for "essay review," etc. And over at the IECA's website, I find 449 members listed as providing college-admissions consulting.

So, now my anxiety ratcheted up still further because it would appear that my SIC code search, which yielded 327 firms, didn't pick up all the consulting firms. HECA lists 811. And even if we assume that the IECA has many individual members whose companies are included in my SIC-search results, I can't be sure that there aren't lots of single-person firms that the IECA list includes and that don't appear on my map of SIC-search results. But that's okay.

If I were doing a serious article here about the geographic distribution of such consulting businesses in the U.S., I would take the time to cross-check these different lists and then add missing data points by hand to my map. (I say "by hand" because the HECA and IECA websites don't make it possible to download their data in bulk, so one would have to do the crosschecking and adding on a per-case basis.) But my purpose here isn't to do an authoritative, defensible piece on admissions-consulting businesses. I'm just taking an initial stab at seeing how hard it is to get reliable data on one very small business sector. I think we can agree that it's not easy.

That said, there's another way of seeing whether the apparently-incomplete SIC data are, at least, in synch with some other universe of data about admissions consulting. Instead of painstakingly transcribing the names and full addresses of particular firms and individuals from the HECA website (which has the larger list of the two), I decided simply to make a spreadsheet of HECA's 800+ entries, noting only the cities and states of members, and then map those counts to see if the distribution comports with the SIC map. Here are the results. And, as you can see, the geographic distribution is pretty much the same. (The relative size and color-intensity of the bubbles indicate the numbers of firms in an area.)

That still leaves us with the question of whether the presence of these college-admissions-consulting companies in an area is a good indicator of, or proxy measure for, social anxiety about college admissions. I don't know. What do you think? What are some other indicators on which we might try to find mappable data?

To contact me, write TierneyJT at gmail.

*You might wonder why you should care what steps I went through. Probably you don't—and shouldn't. But maybe you're part of the small minority who do. One aspect of our effort with the American Futures project is to see how digital mapping can be helpful to journalists, academics, and other generalists in their efforts to explain the world around them. We already know that people in the hard sciences find this technology useful and essential. We're trying to see how the rest of us can use it—and to shine some light on how to do it.